By Camden Donohoe

It has always been a great pleasure of mine to witness one punch above their weight. This, I’m sure, can partly explain my fascination with the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has so far proven itself to be one of the great underdog stories of modern international politics. Incidentally, this summer I have had the unique opportunity to examine this conflict quite closely through my participation in a program called the “NATO Field School”, a Canadian-based university course that guides a cohort of undergraduate and graduate students through a handful of NATO countries in Europe to draw academic awareness towards the fields of security and defense. The first stop for us this year was Riga, Latvia, which received us, understandably considering the events that were and are transpiring mere kilometres from their borders, rather tensely.

The hotel we were staying at was in a district called Maskavas Forstate which, as we were swiftly notified of by some of the more anxiety-prone students, is widely regarded as one of the worst neighbourhoods in Riga. Upon our arrival, our worries surrounding this discovery were eased slightly by a plaque in the hotel lobby which read “we are proud to be located in the third safest district in the region”. However, whatever consolation we drew from such a boast was short lived, as we soon discovered that there were only six districts in Riga to begin with, a fact which would reasonably suggest that the hotel was also located in the third most dangerous district. But what is truth to get in the way of a good boast. In actuality, the area turned out to be perfectly fine, save for a few run-down residential buildings and uneven cobbled roading, and served as an excellent base of operations from which we could further our understanding of NATO’s eastern European defense strategy.

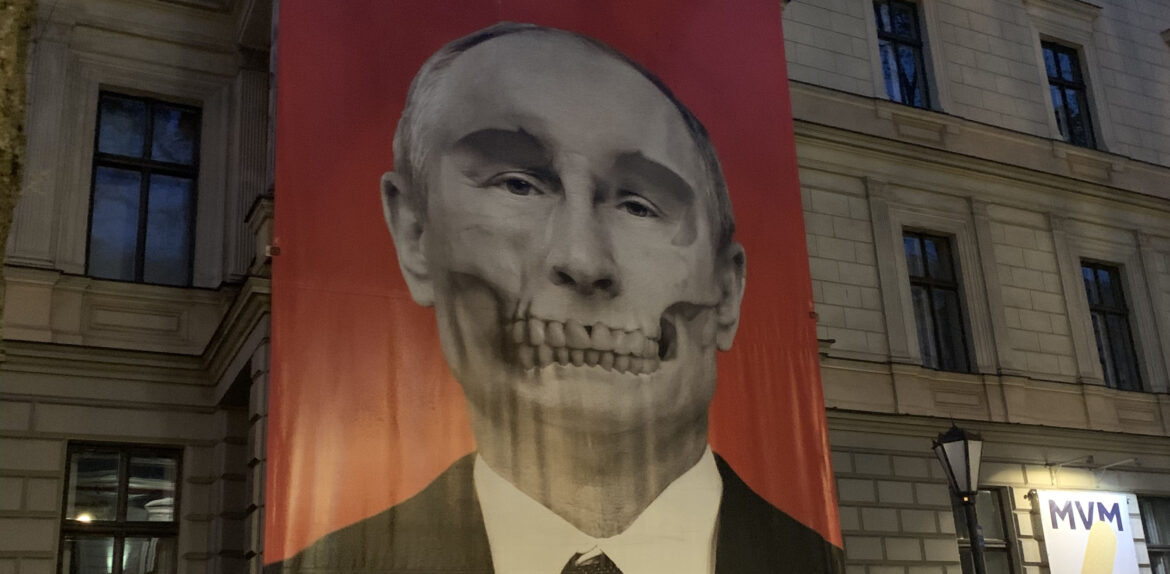

While the region itself was safe, the social and psychological effects of the war next door were made immediately obvious to us. One could hardly walk a few blocks without catching a glimpse of a Ukrainian flag blowing proudly in the wind, a street art installation drawing attention to the various humanitarian horrors of the invasion, or a vulgar piece of wall graffiti expressing general contempt for President Putin and his enablers. In fact, Putin mockery seemed to be a town-favourite, with one of the more memorable displays being an enormous banner hanged directly opposite to the Russian Embassy depicting a portrait of the President with a skull superimposed over his face.

While initially nerve racking, the experience turned out to be deeply informative and rewarding. We not only had the unique opportunity to peer behind the curtain (at least to some extent) to observe NATO’s strategic decision-making process, we were also able to interact with the individuals who these decisions will affect the most. It impressed upon us that we are not simply playing in a world of academic abstraction, but on in which real human lives are at stake, a fact that is regretfully forgotten all too often.